|

|

Entries

tagged as 'Leo Hamson'

As a postscript to our series on Leo Hamson, here are a few additional details. Archives Canada includes a page on Ruth and Leo Hamson. Some excerpts:

Follow the link for more details. Ruth wrote a book: Staying Alive - Tracing the Adventures of George Cornwell & W. Scott Pitzer. I found details via a used copy available from Gallowglass Books and at AbeBooks

Here is final part in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (minor typos corrected) (The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.) EpilogueLong years passed. It was not until the fall of 2001 that the National Film Board of Canada asked me to participate in a film by German-born film-maker Eva Colmers of Edmonton, along with a number of former German POWs she had located. Some of them have since passed away. It was a stunning moment on Dec 21, 2001 when director Eva Colmers brought me face-to-face for the first time in 56 years with former Oberleutnant Siegfried Osterwoldt, and had us shake hands on camera. Unknown to each other, we had been living in Edmonton for many years. Now we are close friends, trying to make up for lost time. Titled “The Enemy Within” these are the stories of German prisoner-of-war camps in Canada told in our own words. The film opens in Regensburg, the lovely old German city on the Danube, and the original home of Eva Colmers. She went back to interview her father, a former POW in Lethbridge. As a child, Eva had heard her father many times speak gratefully of the humane and very correct treatment he had received as a prisoner of the Canadians. It was this memory that had inspired Eva Colmers to make this historic film. Also present at the filmed meeting in Regensburg was Eva’s uncle, who had been taken prisoner on the Eastern Front where millions died and where the soldiers of neither side had any protection from the Geneva Convention. At Stalingrad and countless other battles on hundreds of miles of battlefront, hundreds of thousands of exhausted German soldiers fell into Soviet captivity. Only a very small number survived execution, starvation, and years of brutal slave labour to see their homeland again. The voice of Eva’s uncle chokes with emotion as he recalls his determined struggle to survive and see his family again. The contrast in the experience of the two brothers is profound beyond words. Large numbers of those held captive in Canadian camps were so impressed with their treatment that they could hardly wait to return to make Canada their home. One wonders if any former prisoners of the Soviets did likewise! Few Canadians today are aware of this episode in our history. After seeing the theatre screening of the film, my academic friend Dr. Don Kvill declared, “That made me really proud to be a Canadian!” Indeed, we should take pride in the fact that in those dark and desperate times when other nations lost their humanity and forgot the meaning of civilized behaviour, we did not. War and hatred go hand in hand. It is the real test of any people when they can treat their defeated enemies with humane decency whether they have signed a convention or not. “The Enemy Within” won the top award in an international “World Visions” festival of documentary films in competition with 66 other films. It received its television premiere on the History Television channel September 12th, 2004. The rest, as they say, is history. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission

Here is part 9 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (minor typos corrected) (The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.) A Face From the Distant Past - A Strange EncounterYears passed, memories receded, and I never met anyone again who had been at Wainwright on either side of the wire - until an amazing encounter in 1967. That year I was wandering Europe on my own, marvelling at the incredible recovery from the devastation of the war. I had gone down the Rhine by ship to Koblenz and transferred to a smaller boat on the Moselle, bound for Trier to see the impressive Roman remains there. I was the only passenger for the first part of that Sunday morning as we stopped at many pretty villages to take on or discharge freight. Alone, I sipped glasses of Moselle wine as I admired the stunning scenery. Then at one town a boisterous group obviously on an outing swarmed aboard laden with picnic baskets. Soon an accordion was unpacked and everyone joined in rollicking German songs. They noticed me watching from a corner table and insisted that I join them, fascinated to learn that I was a Canadian. One man, about my own age, fetched the accordion case and used it as a drum. Something about him, something vaguely familiar, held my attention. He had a great scar on his face as though part of his jaw was missing. During a lull in the festivities, he approached me on the outside deck and said that he had been in Canada once and had enjoyed our hospitality. Guardedly, I asked him when and where. “I was a prisoner-of-war,” he grinned, “In Alberta.” I sucked in my breath. “In what camp?” “Wainwright” Then I remembered the Luftwaffe fighter pilot who had part of his jaw shot away just as he bailed out of his crippled Messerschmitt over England. “Do you remember,” I exclaimed, “how many times we stood as close to each other as we do now in the daily prisoner count at Wainwright?” He stared at me for a long moment and then seized me by the arm. “Come! We must have a drink!” Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission

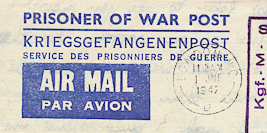

Here is part 8 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (minor typos corrected) (The full set of Recollections is online, with photos.) The Long Road to RepatriationBy March 1946 operations were winding down at Wainwright, and drafts of POWs were being shipped out on the long journey eastward and eventually back to the UK and the large POW holding camp at Lodgemoor near Sheffield. Many had accumulated substantial amounts of personal effects that they could not take with them, such as phonograph records, but mostly things they had made themselves - handicrafts, works of art, suitcases and the like. What they could not take they would have to dispose of. Their only hope of salvaging any value from it was to sell it to the Canadian camp staff for whatever they could get for it. They assembled it in what today would be like a garage sale. For trivial sums I and other camp staff officers purchased a good deal of it, sometimes bidding against each other for the more desirable items. I bought a water-colour of one of the mediaeval gates of Rothenberg-ob-Tauber in Bavaria, a plaster wall plaque of one of Columbus’ ships by one of the few survivors of the Bismark, a well-crafted suitcase made of scraps of wood, a wooden chest as a toy box for my infant son, a leather-covered hand-wound Telefunken portable record player from Col. Hauk, the senior German officer, and a large collection of 78 RPM classical records in pristine condition in fine albums. Many of the POWs had written their names and POW numbers in the albums, crossing out the preceding name as the recordings were passed around as a sort of lending library. Phonograph needles were scarce, and they showed me how they made their own from the thorns of wild roses growing in the area. They sharpened these with sandpaper, and being softer than steel needles, they were kinder to the records. When we were living in our isolated veterans’ settlement in the north with no electricity or access to recreation or entertainment, our group would meet in one of the rough houses we built and after a hard day’s work crank up Colonel Hauk’s Telefunken 78 RPM record player and listen to these prized recordings of classical music and opera, some of them sent from Germany. It enabled us to cling to some vestige of culture as we hacked our homesteads out of the wilderness of Northern Alberta. About five years ago, when I discovered that there was a museum in the old Wainwright railway station devoted to the vanished POW camp, I donated many of these items to their meagre collection, including my Army uniform and some items of military equipment that I had stored away all these years. I still have the wall plaque and most of the record collection in excellent condition. Being 78 RPM they are never played now. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission Here is part 7 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (minor typos corrected) (The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.) A Bitter Memory of a Personal FailureI struck up a friendship with one officer whom I saw frequently because he worked in the Orderly Room. He spoke perfect English, the result of being educated in England. He was Oberleutnant Hans Bauermeister, and had not been a POW as long as most of the others because he was captured in Normandy in June 1944. He had a great desire to stay in Canada and asked me how this could be arranged. I told him that unfortunately we could not just fling open the gates and let them walk away now that the war was over. They would have to be transferred back to the custody of the British in England, and eventually repatriated to their homeland and demobilized. Then perhaps they could apply and join the queue of millions of other homeless refugees and civilian war victims wanting to emigrate to Canada and other parts of the world. I also told him that he would have to accept the fact that there would be some bitterness toward members of the armed forces of our recent enemies, and that they would be at the bottom of the list until those feelings gradually melted away. He was crestfallen when I told him this, but clearly understood. He was a cultured and thoroughly decent chap, and I felt really sorry for him. He showed me photos of his elegant former home, a villa near Potsdam with chandeliers and grand piano visible. He also showed me a photo of his wife, an extraordinarily beautiful woman whom he said had been a film actress. He said he had learned that his home had been wrecked and looted by Soviet troops and his wife and children had disappeared. I gave him an address where he could reach me when I myself was discharged, and promised that I would provide any assistance I could such as a character reference should he decide to emigrate to Canada. Months later, when I was in a remote wilderness area of the Peace River District with a group of other discharged Canadian officers in a Veterans’ Land Act co-operative land development project, I received a “Kriegsgefangenenpost” (Prisoner-of-War Post) from Lt. Bauermeister mailed from Lodgemoor, the large POW holding camp near Sheffield, England. The finely-crafted writing on the camp-issue postcard is almost microscopic. His wife and one son had survived, but while still in Canada he learned that his second son had died a year before. His wife was working on a farm with little food and no money in the Soviet Occupation Zone, struggling to feed the extended family. He begged me to send food parcels to his family, and gave me two addresses - one to his mother in the Russian zone of Berlin, and the other to his brother in the U.S. Zone. He gave me the address of an organization to which I could send money, and they would provide and ship the food parcels. I mentioned this postcard to my ex-officer partners. Today I profoundly regret doing that. The trauma of Normandy was still fresh in their minds. Two of them had been severely wounded - one of them, a major, while getting his tank squadron ashore on D-Day in an action for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. They were outraged that this recent enemy should beg for food from me when millions of victims of the Nazis were starving and homeless. They made it clear that I would be in serious trouble with them if I complied with Bauermeister’s plea. I did not answer it, and put the postcard away with feelings of great discomfort. Some months later I received a lengthy illicit letter from the same camp. He begged me, in any reply I might make, not to refer to the fact that he had written a full letter rather than the officially-allowed post card. I think they were allowed two per month. I cannot imagine why, with the war long over, the British would continue with such harsh restrictions on letter-writing by these lonely men, most of whom had been prisoners for years far from their homeland and families. There could be no security threat in their letters, now that Germany had surrendered long before, After all, they were defeated soldiers, not criminals. He remembered fondly the many pleasant conversations we had while working in the Orderly Room at Wainwright POW Camp. He went into some detail about his family and their condition in Germany. He said he had sustained a crushed thumb while working on a farm with other POWs near Sheffield, and was in hospital, greatly chagrinned that after being unscathed in five years of war he should be injured as a POW a year and a half after fighting ended. In this letter he made two remarks about himself that today bring a lump to my throat when I read them - “More and more I have the intention to emigrate with my family and my brother to your country because our future in Germany will be darker and darker and we do not see any hope to live in Europe. Is any chance for this idea in a reasonable space of time for the hated Germans? Please let me know your opinion in this affair. It is very urgent for me.” And… “At last, please remember if you want, and if you have time enough for a man who is unfortunately a German!” Deferring to the strong feelings of my partners with whom I had to live, I did not answer this letter either. Later I received a third letter, this one from Washington D.C. dated 21 Jan 1947. The writer was Herbert William Hirsch, resident in London, but temporarily in Washington on a mission for the British Government. In his surreptitious letter, Hans Bauermeister had advised me that I would be hearing from his old friend and former pre-war boss when Hirsch was director of a large manufacturing concern in Berlin. He had left Germany and moved to London in 1936 (a wise move for him!). He said that Mr. Hirsch would be at liberty to write more about his former employee’s problems than could be written on a POW postcard. The pleas for help were repeated in a very dignified way. This letter too I put away and did not answer. Today, when I look at these letters, my eyes well with tears. How I wish I could turn back the years and set things right! I had turned my back on a man in distress whom I had promised to help. What if he was a former enemy officer? A promise is a promise, and under the officer’s code of honour, it should have been kept. I can rationalize now that conditions had changed, that I and my partners and our families were facing unforseen hardships in a remote wilderness and having difficulty feeding ourselves, and there was the unforgiving attitudes of my fellow-officers who had suffered much on the battlefields of Europe. But that does nothing to diminish my feelings of guilt. I had betrayed a trust for the only time in my life. I have helped numerous people over the years, including some who did not deserve it, but failed one of the most deserving of all for reasons that were weak and invalid. I have often wondered what became of Oberleutnant Hans Helmut Bauermeister. Did he succeed in making a good life for himself and his family in spite of my failure to help him? Did he ever make it back to Canada? Could he still be alive? If we met, how would I explain what happened? I have learned from another former Wainwright POW, Siegfried Osterwoldt, that there is a society of former POWs in Germany and this dwindling group of elderly German veterans meets once a year and keeps a roll of their names. Inquiries do not reveal the name of Hans Bauermeister. He haunts me still. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission Here is part 6 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (minor typos corrected) (The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.)

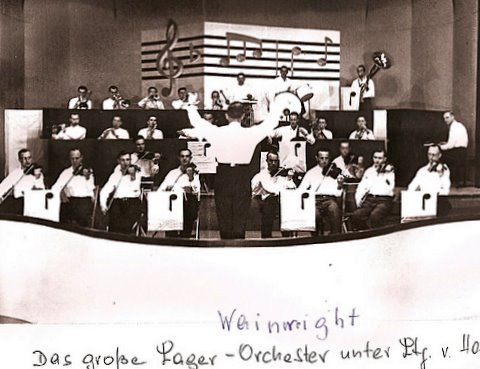

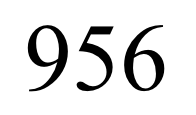

Photo caption: "Das große Lager-Orchester unter Ltg. v. Ha" (?)

Making the Best of Lost YearsI spent no more time than I had to inside the stockade, being pre-occupied with concerns about my own future. As a result, I have few memories of the daily routines of the POWs. When we did go inside the wire, we left our weapons outside. I recall that many of the prisoners kept fit and occupied with sports, while others created handicrafts with amazing skill and ingenuity. Quite a number diligently studied a variety of university-level subjects in make-shift classrooms. In a large group of well-educated members of the Officer Corps, a significant number of former high school teachers and university professors could be found. Occasionally I would make brief visits to one of these classes and stand unobtrusively at the back of the room. Classes in English and mathematics were very popular. Once I noticed a teacher trying painfully to write on a blackboard with a tiny stub of chalk. On my next trip into town I stopped at a school and called on the principal. When I explained things to him, I had no difficulty obtaining a whole box of chalk packed in sawdust - a neat wooden box with a slide top. When I presented this to the struggling POW teacher, his eyes widened as though I had given him a box of gold. I remember one POW who had been an opera tenor. His barrack-mates objected and evicted him when he did his vocal exercises, running up and down the scale. He would stand alone at night in the farthest corner of the compound, his fine voice soaring in the darkness. I made a point of guessing when he would be out, so that I could go to the nearest guard tower to watch and listen to him as he broke into some romantic lieder. There was something unbearably poignant and heart-rending about his lonely performance, singing to the unheeding barbed wire fence in this wintry land so far, so very far, from his homeland. I wondered what operas he had performed, and in what grand opera houses across Europe. He had survived. But I thought of the countless others like him, our brightest and best in every field of endeavour, on both sides of this conflict, who could have done so much to advance our civilisation, but who perished in the furnace of war. Musical instruments and phonograph records were supplied by the YMCA and orchestras were formed. Sadly, I cannot recall hearing them perform. Likely I was always elsewhere on those occasions. Recently, in discussing this with Siegfried Osterwoldt, I learned that one POW had been the director of a school for symphony orchestra conductors in Germany. He quickly formed a 45-piece orchestra and drove them with military discipline as they performed Beethoven and Mozart with a high degree of excellence. That was in Camp 44 at Grande Ligne, Quebec, where Mr. Osterwoldt and many others were held before being moved to the newly-built camp at Wainwright. There was a good library, and some POWs became very proficient at repairing and re-binding books. Handicrafts were popular pastimes, and beautiful art-works in painting, sculpture and wood-carving were produced with amazing skill. They could make useful things out of almost any kind of scrap material. Others retreated to their quarters with text-books, diligently studying for some future profession when they were finally released into an uncertain world. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission Here is part 5 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (minor typos corrected; Col. Hauk might actually be 'Hauck') (Update: The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.) The Ritual of the Daily Head CountI shall never forget my first participation and supervision of the daily head count. As it was winter, the POWs were assembled in parade formation in the large drill hall. Some distance away two guards stood facing each other two paces apart. In line with them and about twenty feet further along, stood a third guard. I paced slowly about watching the procedure and looking important as the duty officer. As our bored charges filed in and formed up, I eyed them with a curious mixture of curiosity, awe, respect, and resentment. We had just come through the greatest man-made catastrophe ever inflicted on humanity, and for us these were the guys that did it. Did those Luftwaffe airmen lined up over there take part in the blitz against defenceless, peaceful Rotterdam, rain bombs on civilians in London Bristol, and scores of other cities, and devastate non-military cultural centres like Bath, Exeter, and Canterbury? I thought of all the friends and class-mates I had lost. I had to struggle to repress these thoughts and focus on the job I had to do. I learned later that some of these men had been prisoners for five years - most of the war - and could not have been involved in the later horrors. Large numbers were members of the Afrika Korps, captured in North Africa after the defeat of Rommel in 1942 and 1943. When they had all formed up, nearly a thousand German officers from all branches of the service, they made quite a spectacle in their various uniforms. I wondered why some were immaculately turned out with their medals and decorations as though for inspection by the Fuhrer, while others looked sloppy and careless in old sweaters and shirts. Were the former the career officers, and the latter the unwilling who had been swept up in the war? Some chatted with those next to them, others read books or magazines, while still others stared vacantly at the floor or ceiling. They looked very different from the disheveled, hungry, battle-shocked prisoners in tattered uniforms that we had rounded up when German resistance collapsed. When all were assembled, the sergeant barked an order and the first rank of prisoners filed between the two guards facing each other, and then past the guard further on. Each guard silently counted. When that rank was finished and formed up at the far end of the drill hall, all three guards compared their counts. If they disagreed, they were marched though again. I then entered the figure on my clip-board. The total of POWs varied slightly from time to time, but during my tour of duty it was 956. That number is burned in my memory. God help us if we could only find 955! That total would never be paraded in the drill hall. Some would be on sick list, others at work in such places as the kitchen. Runners would make the rounds to include them in the total. During the count, Col. Hauk, the senior German officer responsible for discipline, and spokesman to the Canadian commandant, stood on the stage. The prisoners would not be dismissed until we were satisfied that all was in order. Any count disagreements or delays meant they had to stand there for long periods, and this of course irritated them. I was told that while the war was still on, some prisoners passing by the counters would quicken their pace and even start doubling up to confuse and harass their guards. But unless this was a ploy to cover and gain time for an escaper, it tended to raise the ire of their fellow prisoners, because they all had to stand there while the count was repeated. On one memorable occasion we were one short. We counted them all again, and scouts, including some POWs, were despatched on a search of the camp. As tension and the tempers of the standing POWs mounted, they glanced through their ranks speculating who was missing. A murmur rippled through to me…. “It’s the little engineer!” Then I remembered our most unusual prisoner - unusual because he was a civilian and no-one seemed to know why he was in this camp for German officers. The story was that he was the engineer on a train carrying German troops that got shot up by R.A.F. Typhoons and was then surrounded and captured by British troops. They did not know what to do with the civilian locomotive driver, so scooped him up with the military prisoners. He ended up in Wainwright. He was a very short stocky man, and naturally conspicuous among his uniformed fellow prisoners. As time dragged on and some of the prisoners sat on the floor, Col. Hauk paced the stage angrily, and asked to speak to me. He said that since we knew the identity of the missing man, there was no reason for not dismissing the parade. I refused. Standing Orders had to be followed. Finally, the large double doors of the drill hall opened, and we were treated to a most unusual sight. Silhouetted against the outside daylight, two large Germans marched in. Between them they carried the little engineer by the arms, his legs pedalling the air off the ground. The ranks of the POWs parted to let them pass, and they hurled epithets at the cause of their inconvenience. They marched right up to the stage and plunked the trembling man on the floor in front of Col. Hauk who glared down at him with legs apart and fists on his hips. It turned out that the searchers had found him sitting fast asleep on the toilet. I dismissed the parade, and as they filed out I walked over to the stage and stood behind the cringing engineer. The colonel looked at me and said crisply, “I shall take care of the matter, Lieutenant.” That was my cue to depart with my clip-board and my assistants, and as I went out the door I glanced back and saw the colonel still glaring down at the wretched engineer, and I wondered what punishment would be meted out. I hoped Col. Hauk had a sense of humour. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission Here is part 4 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (minor typos corrected) (Update: The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.) Dreary Prospects For a POWHowever, any harsh conditions and rigid regulations had softened greatly by the time I arrived at Wainwright. The war had ended several months before, and attitudes had changed considerably. Germany had lost the long and bloody war, and our unwilling guests were no longer considered a dangerous threat to our security. At that point in time, the only possible motive for escape was to become illegal immigrants to Canada, with the hope of melting undetected into our population. All thoughts, for captives and captors alike, were on salvaging all they could from ruined lives. For us, the victors, there were bright hopes in a country that despite the great cost of our victory, was spared the physical blight of war. For the vanquished, there was despair and uncertainty, knowing that their homeland was now largely in smoking ruins. It must have been a terrible thing to have suffered so much on far-flung battlefields and to know that it was all for nothing. They too were victims of the greatest episode of mass insanity in human history. It was not generally realized that officially these men were prisoners of the British, and they were being incarcerated in Canada at the request of the British Government for obvious reasons. In Britain they were short of food and space, and any escapers posed more of a threat to security in what was literally a war zone. Britain retained control, and their wishes had to be complied with. I was not aware at the time of an extraordinarily harsh and pointless order concerning the treatment of POWs that came from Britain after the war ended. I learned of this only recently from the reminiscences of former Wainwright POW Siegfried Osterwoldt. Rations were reduced to 900 calories per day, barely above subsistence level. The reasoning behind this is obscure. Was it to punish the Germans for the starvation and deprivation among war victims across Europe? To let them know what real hunger felt like after living so well on Canadian rations that they had difficulty buttoning their uniforms? I have no idea of what the Canadian authorities thought of this order from the British Government, but under the bilateral agreement the Canadians had no option but to comply. I learned recently that the American government at the same time imposed the same ration restrictions on the thousands of POWs they held in the U.S.A. One thing was certain - with the defeat of Germany and the liberation of our men from their POW camps, there was no danger of retaliation. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission The rations were apparently reduced to the level that prevailed in Germany at the time (due to the extreme food shortages after the war). That was also about what Allied POWs were receiving in German camps towards the end of the war. From his personal contacts with former German POWs (who were generally quite appreciative of their good treatment in Canada), David J. Carter adds:

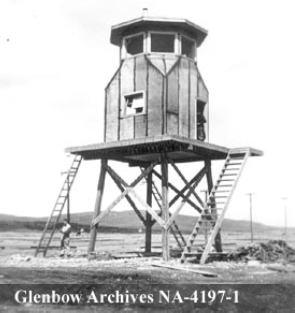

Here is part 3 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (Update: The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.) A Prisoner’s Paradise?The next morning was my first day on the job, and I was told to check all the sentries at the gates and in the guard towers. The towers were quite a climb. I was astounded to see scores of POWs streaming out the open gate of the POW compound carrying skis over their shoulders. NOW what was going on? The tower guard on duty was observing this calmly without a word. I scrambled down from the tower and hurried to the gate and the small building beside it through which the ski-laden POWs were trooping. I saw that each one was signing a form as he passed through. I picked one up and read it. It was printed in both English and German. I wish now that I had kept one. To the best of my recollection it said something to the effect… “I declare on my honour as a German Officer that I will not attempt to escape while outside the POW compound on this parole, that I will stay within the prescribed area, that I will not approach any civilians, that I will not go near the railroad tracks, and that I will return and report in to the gate not later than 4.00 o’clock. I acknowledge that any violation of this parole may result not only in the prescribed punishment for me but cancellation of this privilege for all German officers in this camp indefinitely.” Thereafter I became accustomed to watching them with my binoculars from the towers as they enjoyed themselves on the gentle slopes with skis supplied by, I believe, the Y.M.C.A., Red Cross, and other charitable organizations. Was this a prison camp or a resort? I often observed them stopping to look at their watches, wondering if they had time for one more slide down the slope before time was up. We had warned them that the gate would be closed at the appointed time, and anyone locked out would be declared an escapee in very serious trouble and in danger of being shot. The siren would then sound to alert the whole camp and army base. For those not involved in skiing, there were escorted exercise walks in large groups outside the wire. Not once was this parole ever violated deliberately. In the curious irony governing prisoner-of-war camps and the Geneva Convention, the parole ended as soon as they were back inside the stockade. Then they were legally and honourably entitled to use all their wits, guile, and resources to attempt escape, and in every way give their captors as much trouble as possible. Some considered it their duty, as they were still soldiers at war with their enemies. They could be shot while fleeing, but not after they had surrendered. Thirty days solitary confinement was the usual punishment for escape attempts. These were the rules of the game for both sides in World War II for signatories to the Geneva Convention. Compliance was monitored by a neutral “Protecting Power”, usually Switzerland, and reports were made to the respective governments of the belligerents. Generally, the rules were adhered to with correctness by both sides, but there were a number of tragic and brutal lapses involving mass murder of helpless Allied prisoners, including Canadians in Normandy, by the Nazi S.S. and the Gestapo. As is usual with crimes of the winning side, much less is known of the hundreds of thousands[1] of German prisoners left to perish in an open field surrounded by barbed wire without shelter, food, or water after the final German surrender on May 8, 1945. It is alleged that this apparent war crime was carried out on the orders of the Allied Commander-in-Chief, American General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission [1] This allegation was made prominent in a book published in 1989, and refuted by a panel of historians in 1990 (published as a book in 1992). From a subsequent article: "There was never any serious disagreement that the German POWs were treated badly by the U.S. Army and suffered egregiously in these camps in the first weeks after the end of the war. ... But there was NO AMERICAN POLICY to starve them to death as Bacque asserts and NO COVER UP either after the war." Here is part 2 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (Update: The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.) I opened the series last week with his story of Klaus Conrad's escape, though this entry actually comes first. I think it must have taken place in the Winter of 1945-1946, i.e. after the war was over but before POWs were sent back to Germany. My Introduction to a World Behind Barbed WireI cannot now remember the date that I was posted to the Wainwright POW camp in Northern Alberta other than it was in the depth of winter. And I am not certain to this day that it was because they actually needed me, or because they did not know what else to do with a surplus 25-year-old artillery lieutenant recently returned from overseas who was declining to take his discharge but still had to earn his keep. On arrival at the railroad station, I was met by a private of the Veterans’ Guard Of Canada driving an open jeep and my trunk was slung in the back. As we entered the precincts of the camp in brilliant winter sunshine, I saw for the first time the great prisoner-of-war stockade consisting of two high fences about twelve feet apart. The massive posts and criss-crossed barbed wire enclosed several acres, with neat rows of barracks of the style that was standard for the Canadian Army, an equivalency for the POWs as prescribed by the Geneva Convention. At intervals along the fence were the formidable guard towers, large structures with several flights of wooden stairs to reach the top-most glassed-in deck from which the armed guards kept watch. It was a chilling sight. We passed a hockey rink set up outside the barbed wire stockade. A vigorous game was in progress. I commented to my driver, “Oh! I see you play hockey here.” “Yes sir!” he responded cheerily, “Today the guards are playing the POWs” I was too shocked to make any reply. Evidently fraternization with the enemy was alive and well in Wainwright Prisoner-of-War Camp 135. After getting installed in my room in the Officers’ Quarters, I went to the H.Q. building and reported to Major Shanks, the commandant of Veterans’ Guard of Canada No. 27 Company. While eyeing me up and down, he noted the empty holster on my belt and asked me where my revolver was. I said that after returning from overseas I saw no further need for lugging the heavy thing around and turned it in to the quartermaster in Calgary. He said, “Well, you will need one here. Go to the Q.M. Stores and draw one!” He indicated a building in the distance on a slight rise. On the road to the building, I saw three figures approaching, marching briskly. As they passed me, they saluted me smartly. I was stunned to realize they were German officers, and we were outside the stockade! I had automatically returned their salute, and then remembered the order of the vengeful General Eisenhower overseas that we were not to return the salutes of German prisoners. I had felt uncomfortable and embarrassed by this ban on what had always been considered an honourable military courtesy, even for a defeated enemy. When I entered the building, I found the usual quartermaster stores with shelves loaded with clothing, boots, equipment, tools, and weapons, all behind a long counter. At first there appeared to be no-one there, but suddenly a man at a desk behind the counter leaped to his feet and saluted me. I could hardly believe my eyes. He was dressed impeccably in the uniform of a German captain. Something was terribly wrong here. Mindful of what I had come for, I stammered, “There must be some mistake.” and turned to leave. Before I could reach the door, he called out in excellent English “You must be Lieutenant Hamson. I had a phone call from the Orderly Room about you. You have come for this.” He then reached under the counter and placed a regulation Smith and Wesson .38 caliber revolver on the counter. From a drawer he withdrew a box of cartridges, opened it to ensure that it was full and correct, and pushed the two items toward me. Then, as I stood there speechless, he pushed a book toward me. “Please sign here.” In a state of shock, I fumbled as I stowed the revolver in my holster, put the cartridges in my belt pouch, and walked unsteadily out the door. What kind of a place was this? Alice in Wonderland? A prisoner issuing me a GUN? When I went into the Orderly Room, I was in for a further shock. The people working busily at filing cabinets, typewriters and the switchboard were German officers. A Veteran’s guard lounged in a corner, smoking a pipe and reading a newspaper. When I encountered the commandant later, I let him know of my total astonishment to find the place apparently being run by the prisoners. “Of course!” he said, “The ones you see outside the stockade have signed a parole and they love having something useful to do. They are very good at it too…Teutonic efficiency and all that sort of thing, you know. And that gives us more time to spend in the mess drinking beer!” He then glanced at his watch. “My goodness! Time for four o’clock tea! Come along!” Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission Lieutenant Leo Hamson returned to Canada after fighting in Europe, and was sent to Camp Wainwright as a guard. This entry is the first in a series, reprinted with permission. (emphasis added; 1 paragraph break added; 1 typo corrected) (Update: The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.) A Brilliant EscapeAt dinner one night in the Officers’ Mess, I was regaled with the story of a successful escape by two POW officers that occurred when Wainwright first opened for business. The tale was told by the Veterans’ Guard officers with great relish and obvious admiration. It seems that a trainload of POWs arrived before the camp construction was quite finished, much to the consternation of the senior Canadian officer. The buildings were complete, but the stockade fences were not. The barbed wire was still being strung by the army engineers. The exasperated Canadian colonel ordered the POWs herded into their barracks with armed guards at the doors until the wiring was finished. The POWs watched the work from the windows. They noted that the khaki denim material of the work coveralls worn by the Canadians was of the same material covering the mattresses on their double-decker army beds. The senior German officer put out a call for anyone with tailoring experience. Hans Pfeffel stepped forward, and very soon had fashioned passable replicas of the coveralls. These were donned by Lt. E. Meuche and Lt. Klaus Conrad. While the others feigned a scuffle among themselves to distract the guards, these two slipped out and joined the fencing crew, giving a friendly wave to the tower guards as they passed under them. The guards cheefully returned the gesture. They unrolled a large spool of barbed wire along the line of posts, but veered from the line towards a copse of trees, then bolted unnoticed. They reached the railroad tracks and leaped aboard a passing freight train. Knowing nothing of Alberta geography[*], the next train they boarded was heading north to Lesser Slave Lake before they realized they would never reach the Fatherland that way. They caught a south-bound train, and were not apprehended until a month later in Gary Indiana. They were not returned to Wainwrght, but to the camp at Gravenhurst. There was a strange post-script to this story. Hans Pfeffel returned to Canada, settled in Coaldale, in Southern Alberta, opened a clothing store, and raised a family. He had a major part in the National Film Board documentary “The Enemy Within,” which I shall refer to later, and also provided some harmonica background music for the film. As my son-in-law now residing in England was born and raised in the small town of Coaldale, I was amazed when my inquiries revealed that the two families had been friends for years. Last year, although battling terminal cancer, Hans was determined to meet us, and made the very long journey to Edmonton with his wife, daughter, and son-in-law. We were joined at a luncheon in our garden by another former Wainwright POW, Siegfried Osterwoldt and his wife, and by Eva Colmers, who made and directed the film. A few weeks later, Hans passed away. We shall be forever grateful for his valiant effort in making the arduous journey that made possible an unforgettable reunion after nearly six decades. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission * I think that heading north was planned, but in any case it's great to have an account direct from the Canadian side. |