|

|

August 2010 Archive

Last Friday's book excerpt mentioned that many POWs worked in the logging industry. Fawcett Lake is in Alberta; here's some information from the other side of Canada.

It's a long article, with lots of historical details.

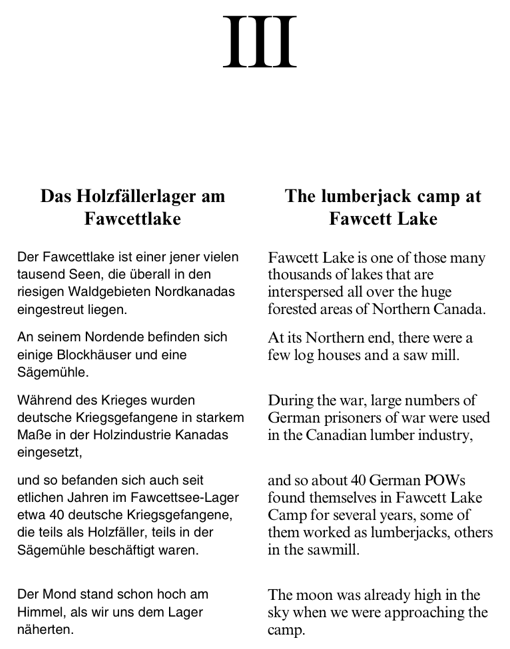

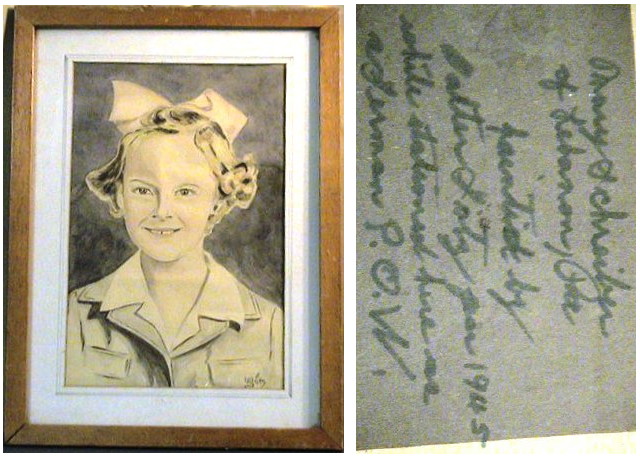

Here is part 8 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (minor typos corrected) (The full set of Recollections is online, with photos.) The Long Road to RepatriationBy March 1946 operations were winding down at Wainwright, and drafts of POWs were being shipped out on the long journey eastward and eventually back to the UK and the large POW holding camp at Lodgemoor near Sheffield. Many had accumulated substantial amounts of personal effects that they could not take with them, such as phonograph records, but mostly things they had made themselves - handicrafts, works of art, suitcases and the like. What they could not take they would have to dispose of. Their only hope of salvaging any value from it was to sell it to the Canadian camp staff for whatever they could get for it. They assembled it in what today would be like a garage sale. For trivial sums I and other camp staff officers purchased a good deal of it, sometimes bidding against each other for the more desirable items. I bought a water-colour of one of the mediaeval gates of Rothenberg-ob-Tauber in Bavaria, a plaster wall plaque of one of Columbus’ ships by one of the few survivors of the Bismark, a well-crafted suitcase made of scraps of wood, a wooden chest as a toy box for my infant son, a leather-covered hand-wound Telefunken portable record player from Col. Hauk, the senior German officer, and a large collection of 78 RPM classical records in pristine condition in fine albums. Many of the POWs had written their names and POW numbers in the albums, crossing out the preceding name as the recordings were passed around as a sort of lending library. Phonograph needles were scarce, and they showed me how they made their own from the thorns of wild roses growing in the area. They sharpened these with sandpaper, and being softer than steel needles, they were kinder to the records. When we were living in our isolated veterans’ settlement in the north with no electricity or access to recreation or entertainment, our group would meet in one of the rough houses we built and after a hard day’s work crank up Colonel Hauk’s Telefunken 78 RPM record player and listen to these prized recordings of classical music and opera, some of them sent from Germany. It enabled us to cling to some vestige of culture as we hacked our homesteads out of the wilderness of Northern Alberta. About five years ago, when I discovered that there was a museum in the old Wainwright railway station devoted to the vanished POW camp, I donated many of these items to their meagre collection, including my Army uniform and some items of military equipment that I had stored away all these years. I still have the wall plaque and most of the record collection in excellent condition. Being 78 RPM they are never played now. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission Chapter III Das Holzfällerlager am Fawcettlake Der Fawcettlake ist einer jener vielen tausend Seen, die überall in den riesigen Waldgebieten Nordkanadas eingestreut liegen. An seinem Nordende befinden sich einige Blockhäuser und eine Sägemühle. Während des Krieges wurden deutsche Kriegsgefangene in starkem Maße in der Holzindustrie Kanadas eingesetzt, und so befanden sich auch seit etlichen Jahren im Fawcettsee-Lager etwa 40 deutsche Kriegsgefangene, die teils als Holzfäller, teils in der Sägemühle beschäftigt waren. Der Mond stand schon hoch am Himmel, als wir uns dem Lager näherten. The lumberjack camp at Fawcett Lake Fawcett Lake is one of those many thousands of lakes that are interspersed all over the huge forested areas of Northern Canada. At its Northern end, there were a few log houses and a saw mill. During the war, large numbers of German prisoners of war were used in the Canadian lumber industry, and so about 40 German POWs found themselves in Fawcett Lake Camp for several years, some of them worked as lumberjacks, others in the sawmill. The moon was already high in the sky when we were approaching the camp.

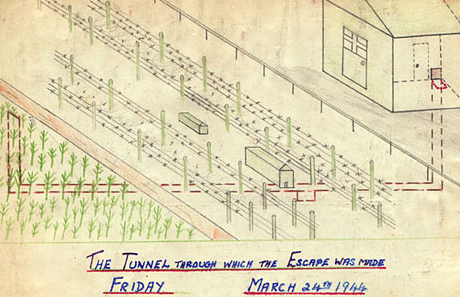

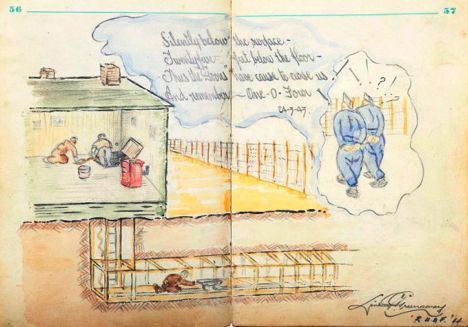

"Why? Why does a POW escape anyway, when he suffers no physical emergency and everything is done to ease psychological stress? Why does he trade a life with adequate food in well heated shelter for the danger and hardship of an almost impossible escape?" (pages 84-85) Image adapted from ian_munroe at Flickr. Music from Bach's Toccata Adagio Fugue: http://www.musopen.com/music.php?type=piece&id=468 Apropos of yesterday's post, here's another diary from a POW held at Stalag Luft III. Last November, the BBC aired a two-part series on Ted Nestor's War Diary. According to their article:

During his captivity, Nestor kept an illustrated diary. Some of the pages can be seen in an audio slideshow of his daughter telling his story. Author: Richard Turner

Publication: BBC Manchester

Section: News

Length: 635 words

Date: November 23, 2009

In February, Mail Online in the UK published rare WW2 sketches drawn in the diary of a British POW. According to the article:

The diary includes sketches of the tunnels made famous in The Great Escape. Follow the link to see more images. Publication: MailOnline

Section: News

Length: 794 words

Date: February 4, 2010

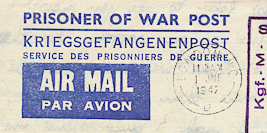

Here is part 7 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (minor typos corrected) (The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.) A Bitter Memory of a Personal FailureI struck up a friendship with one officer whom I saw frequently because he worked in the Orderly Room. He spoke perfect English, the result of being educated in England. He was Oberleutnant Hans Bauermeister, and had not been a POW as long as most of the others because he was captured in Normandy in June 1944. He had a great desire to stay in Canada and asked me how this could be arranged. I told him that unfortunately we could not just fling open the gates and let them walk away now that the war was over. They would have to be transferred back to the custody of the British in England, and eventually repatriated to their homeland and demobilized. Then perhaps they could apply and join the queue of millions of other homeless refugees and civilian war victims wanting to emigrate to Canada and other parts of the world. I also told him that he would have to accept the fact that there would be some bitterness toward members of the armed forces of our recent enemies, and that they would be at the bottom of the list until those feelings gradually melted away. He was crestfallen when I told him this, but clearly understood. He was a cultured and thoroughly decent chap, and I felt really sorry for him. He showed me photos of his elegant former home, a villa near Potsdam with chandeliers and grand piano visible. He also showed me a photo of his wife, an extraordinarily beautiful woman whom he said had been a film actress. He said he had learned that his home had been wrecked and looted by Soviet troops and his wife and children had disappeared. I gave him an address where he could reach me when I myself was discharged, and promised that I would provide any assistance I could such as a character reference should he decide to emigrate to Canada. Months later, when I was in a remote wilderness area of the Peace River District with a group of other discharged Canadian officers in a Veterans’ Land Act co-operative land development project, I received a “Kriegsgefangenenpost” (Prisoner-of-War Post) from Lt. Bauermeister mailed from Lodgemoor, the large POW holding camp near Sheffield, England. The finely-crafted writing on the camp-issue postcard is almost microscopic. His wife and one son had survived, but while still in Canada he learned that his second son had died a year before. His wife was working on a farm with little food and no money in the Soviet Occupation Zone, struggling to feed the extended family. He begged me to send food parcels to his family, and gave me two addresses - one to his mother in the Russian zone of Berlin, and the other to his brother in the U.S. Zone. He gave me the address of an organization to which I could send money, and they would provide and ship the food parcels. I mentioned this postcard to my ex-officer partners. Today I profoundly regret doing that. The trauma of Normandy was still fresh in their minds. Two of them had been severely wounded - one of them, a major, while getting his tank squadron ashore on D-Day in an action for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. They were outraged that this recent enemy should beg for food from me when millions of victims of the Nazis were starving and homeless. They made it clear that I would be in serious trouble with them if I complied with Bauermeister’s plea. I did not answer it, and put the postcard away with feelings of great discomfort. Some months later I received a lengthy illicit letter from the same camp. He begged me, in any reply I might make, not to refer to the fact that he had written a full letter rather than the officially-allowed post card. I think they were allowed two per month. I cannot imagine why, with the war long over, the British would continue with such harsh restrictions on letter-writing by these lonely men, most of whom had been prisoners for years far from their homeland and families. There could be no security threat in their letters, now that Germany had surrendered long before, After all, they were defeated soldiers, not criminals. He remembered fondly the many pleasant conversations we had while working in the Orderly Room at Wainwright POW Camp. He went into some detail about his family and their condition in Germany. He said he had sustained a crushed thumb while working on a farm with other POWs near Sheffield, and was in hospital, greatly chagrinned that after being unscathed in five years of war he should be injured as a POW a year and a half after fighting ended. In this letter he made two remarks about himself that today bring a lump to my throat when I read them - “More and more I have the intention to emigrate with my family and my brother to your country because our future in Germany will be darker and darker and we do not see any hope to live in Europe. Is any chance for this idea in a reasonable space of time for the hated Germans? Please let me know your opinion in this affair. It is very urgent for me.” And… “At last, please remember if you want, and if you have time enough for a man who is unfortunately a German!” Deferring to the strong feelings of my partners with whom I had to live, I did not answer this letter either. Later I received a third letter, this one from Washington D.C. dated 21 Jan 1947. The writer was Herbert William Hirsch, resident in London, but temporarily in Washington on a mission for the British Government. In his surreptitious letter, Hans Bauermeister had advised me that I would be hearing from his old friend and former pre-war boss when Hirsch was director of a large manufacturing concern in Berlin. He had left Germany and moved to London in 1936 (a wise move for him!). He said that Mr. Hirsch would be at liberty to write more about his former employee’s problems than could be written on a POW postcard. The pleas for help were repeated in a very dignified way. This letter too I put away and did not answer. Today, when I look at these letters, my eyes well with tears. How I wish I could turn back the years and set things right! I had turned my back on a man in distress whom I had promised to help. What if he was a former enemy officer? A promise is a promise, and under the officer’s code of honour, it should have been kept. I can rationalize now that conditions had changed, that I and my partners and our families were facing unforseen hardships in a remote wilderness and having difficulty feeding ourselves, and there was the unforgiving attitudes of my fellow-officers who had suffered much on the battlefields of Europe. But that does nothing to diminish my feelings of guilt. I had betrayed a trust for the only time in my life. I have helped numerous people over the years, including some who did not deserve it, but failed one of the most deserving of all for reasons that were weak and invalid. I have often wondered what became of Oberleutnant Hans Helmut Bauermeister. Did he succeed in making a good life for himself and his family in spite of my failure to help him? Did he ever make it back to Canada? Could he still be alive? If we met, how would I explain what happened? I have learned from another former Wainwright POW, Siegfried Osterwoldt, that there is a society of former POWs in Germany and this dwindling group of elderly German veterans meets once a year and keeps a roll of their names. Inquiries do not reveal the name of Hans Bauermeister. He haunts me still. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission Zum Glück war der Trapper selbst sehr redselig, denn er hatte scheinbar selten Gelegenheit, sich zu unterhalten. So erfuhren wir bald alles Wissenswerte über das Land zwischen Athabasca und Peace River, einer Ortschaft einige hundert Meilen weiter nördlich. "Well, boys, ich glaube, wir werden uns bald wiedersehen", meinte der Trapper, als er uns gegen Abend an einem Seitenweg absetzte und machte ein vielsagendes Gesicht. "Was er wohl gemeint hat mit diesen Worten beim Abschied", bemerkte ich nach einer Weile, als wir schon ein gutes Stück waldeinwärts marschiert waren. "Und dieses merkwürdige Mienenspiel um seine Augen, als wenn er ..." Heinz sprach nicht weiter, und jeder hing seinen Gedanken nach; irgendein unangenehmes Gefühl beschlich mich aber, sooft ich an den Trapper dachte. Wir kamen gut vorwärts auf unserem Weg, denn ein Schneepflug hatte den Schnee geräumt; als es zu dämmern begann, waren wir nur noch etwa zwei Stunden von dem Holzfällerlager der Firma Mc. Millan entfernt, in dem wir deutsche Kriegsgefangene wußten. Luckily, the trapper himself was quite chatty, apparently because he seldom had the opportunity to engage in conversation. So we soon learned everything worth knowing about the land between Athabasca and Peace River, a town a few hundred miles farther north. "Well, boys, I believe we will see each other again soon," said the trapper, as he dropped us off at a back road toward evening, and made a telling face. "What indeed had he meant with these words of farewell," I remarked after awhile, as we had already marched a good bit into the woods. "And this strange expression in his eyes, as if he ..." Heinz spoke no further, and we each kept our own thoughts; but an unpleasant feeling crept over me whenever I thought of the trapper. We made good progress on our way since a snow plow had cleared the snow; as twilight set in we were about two hours away from the lumberjack camp of the Mc. Millan Company, which we knew housed German prisoners of war.

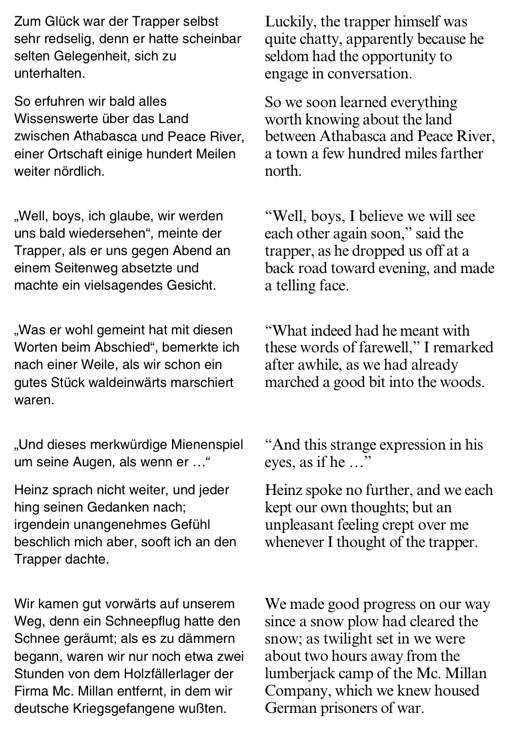

"Why? Why does a POW escape anyway, when he suffers no physical emergency and everything is done to ease psychological stress? Why does he trade a life with adequate food in well heated shelter for the danger and hardship of an almost impossible escape?" (pages 84-85) Image adapted and composited from unplain-jane and jamescridland at Flickr. Music from Bach's Toccata Adagio Fugue: http://www.musopen.com/music.php?type=piece&id=468 Here's a portrait from the same source as yesterday: The Okie Legacy, Volume 8, Issue 39.

(Follow the link to add a comment or contact the current owner.) Text on the back (as best I can read it): "Mary Schreiber of Lebanon, PA painted by Walter Gotz (Götz?) year 1945 while stationed here as a German P.O.W.". I found this oil painting in The Okie Legacy, Volume 8, Issue 39. Here is part 6 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (minor typos corrected) (The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.)

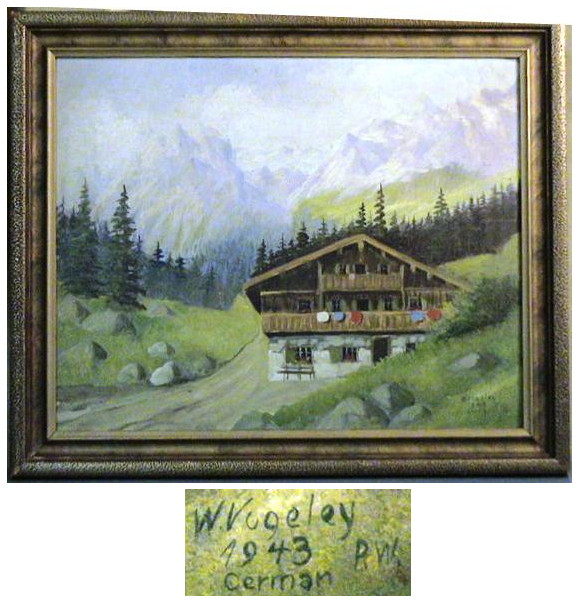

Photo caption: "Das große Lager-Orchester unter Ltg. v. Ha" (?)

Making the Best of Lost YearsI spent no more time than I had to inside the stockade, being pre-occupied with concerns about my own future. As a result, I have few memories of the daily routines of the POWs. When we did go inside the wire, we left our weapons outside. I recall that many of the prisoners kept fit and occupied with sports, while others created handicrafts with amazing skill and ingenuity. Quite a number diligently studied a variety of university-level subjects in make-shift classrooms. In a large group of well-educated members of the Officer Corps, a significant number of former high school teachers and university professors could be found. Occasionally I would make brief visits to one of these classes and stand unobtrusively at the back of the room. Classes in English and mathematics were very popular. Once I noticed a teacher trying painfully to write on a blackboard with a tiny stub of chalk. On my next trip into town I stopped at a school and called on the principal. When I explained things to him, I had no difficulty obtaining a whole box of chalk packed in sawdust - a neat wooden box with a slide top. When I presented this to the struggling POW teacher, his eyes widened as though I had given him a box of gold. I remember one POW who had been an opera tenor. His barrack-mates objected and evicted him when he did his vocal exercises, running up and down the scale. He would stand alone at night in the farthest corner of the compound, his fine voice soaring in the darkness. I made a point of guessing when he would be out, so that I could go to the nearest guard tower to watch and listen to him as he broke into some romantic lieder. There was something unbearably poignant and heart-rending about his lonely performance, singing to the unheeding barbed wire fence in this wintry land so far, so very far, from his homeland. I wondered what operas he had performed, and in what grand opera houses across Europe. He had survived. But I thought of the countless others like him, our brightest and best in every field of endeavour, on both sides of this conflict, who could have done so much to advance our civilisation, but who perished in the furnace of war. Musical instruments and phonograph records were supplied by the YMCA and orchestras were formed. Sadly, I cannot recall hearing them perform. Likely I was always elsewhere on those occasions. Recently, in discussing this with Siegfried Osterwoldt, I learned that one POW had been the director of a school for symphony orchestra conductors in Germany. He quickly formed a 45-piece orchestra and drove them with military discipline as they performed Beethoven and Mozart with a high degree of excellence. That was in Camp 44 at Grande Ligne, Quebec, where Mr. Osterwoldt and many others were held before being moved to the newly-built camp at Wainwright. There was a good library, and some POWs became very proficient at repairing and re-binding books. Handicrafts were popular pastimes, and beautiful art-works in painting, sculpture and wood-carving were produced with amazing skill. They could make useful things out of almost any kind of scrap material. Others retreated to their quarters with text-books, diligently studying for some future profession when they were finally released into an uncertain world. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission Kein Fahrzeug kam um diese Stunde daher. Endlich wurde es Tag. Gleich der erste Lkw, dem wir winkten, nahm uns mit. Immer weiter nach Norden gelangten wir, immer tiefer in die riesigen Waldgebiete Nord-West-Kanadas. Wälder, Wälder, soweit das Auge reichte, dazwischen einige Seen, hin und wieder ein Gehöft, ganz selten eine Ortschaft. Der Urwald begann ... Am Nachmittag erreichten wir Athabasca. Letzter Ausläufer der Zivilisation, eine Sägemühle, ein Kino, eine Bar - und dann beginnt der Urwald endgültig seine Herrschaft. Weiter nach Norden führte nur ein ganz selten befahrener Weg. Es war wirklich ein großer Zufall, daß ein Trapper mit seinem Vehikel daherkam und uns mitnahm. Diese Breiten sind so dünn besiedelt, daß jedes fremde Gesicht sofort auffällt. Wie ein Inquisitor fragte uns der neuigkeitshungernde Mann aus - und was wußten denn wir von der Welt außerhalb des Stacheldrahtes? No car came along at this hour. Finally it became day. The first truck that we waived down gave us a ride. Ever farther to the north we went, ever deeper into the vast forested areas of Northwest Canada. Forests, forests, as far as the eye could see, some lakes in between, now and again a farmhouse, quite seldom a town. The wilderness began ... In the afternoon, we reached Athabasca. The last outpost of civilization, a sawmill, a theater, a bar - and then the wild forest finally began its reign. The only way to go farther north was a rarely used path. It was really a great coincidence, that a trapper came along with his vehicle and gave us a ride. These zones are so sparsely populated, that every strange face immediately stands out. Like an inquisitor, the news-starved man questioned us - but what did we know of the world outside the barbed wire?

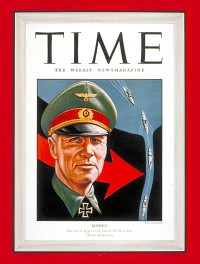

"Sure, we could have made some noise - they would have gotten us out and given us something to drink - but it would have been the end of our escape, the end of our freedom. Our moral stamina was still stronger than the thirst, we still forced ourselves to keep quiet - but how much longer now?" (page 84, second excerpt) Image adapted and composited from jmegjmeg, nattu, leecohen, and onecog2many at Flickr. Music from Bach's Toccata Adagio Fugue: http://www.musopen.com/music.php?type=piece&id=468 Peter Krug's capture and trial was covered in the July 13, 1942 issue of Time Magazine:

The daily count wasn't always sufficient to determine that prisoners were missing.

We've already seen the answer:

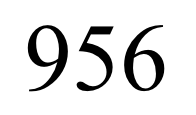

Read Lynn Philip Hodgson's entire article for the rest of the story. Here is part 5 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (minor typos corrected; Col. Hauk might actually be 'Hauck') (Update: The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.) The Ritual of the Daily Head CountI shall never forget my first participation and supervision of the daily head count. As it was winter, the POWs were assembled in parade formation in the large drill hall. Some distance away two guards stood facing each other two paces apart. In line with them and about twenty feet further along, stood a third guard. I paced slowly about watching the procedure and looking important as the duty officer. As our bored charges filed in and formed up, I eyed them with a curious mixture of curiosity, awe, respect, and resentment. We had just come through the greatest man-made catastrophe ever inflicted on humanity, and for us these were the guys that did it. Did those Luftwaffe airmen lined up over there take part in the blitz against defenceless, peaceful Rotterdam, rain bombs on civilians in London Bristol, and scores of other cities, and devastate non-military cultural centres like Bath, Exeter, and Canterbury? I thought of all the friends and class-mates I had lost. I had to struggle to repress these thoughts and focus on the job I had to do. I learned later that some of these men had been prisoners for five years - most of the war - and could not have been involved in the later horrors. Large numbers were members of the Afrika Korps, captured in North Africa after the defeat of Rommel in 1942 and 1943. When they had all formed up, nearly a thousand German officers from all branches of the service, they made quite a spectacle in their various uniforms. I wondered why some were immaculately turned out with their medals and decorations as though for inspection by the Fuhrer, while others looked sloppy and careless in old sweaters and shirts. Were the former the career officers, and the latter the unwilling who had been swept up in the war? Some chatted with those next to them, others read books or magazines, while still others stared vacantly at the floor or ceiling. They looked very different from the disheveled, hungry, battle-shocked prisoners in tattered uniforms that we had rounded up when German resistance collapsed. When all were assembled, the sergeant barked an order and the first rank of prisoners filed between the two guards facing each other, and then past the guard further on. Each guard silently counted. When that rank was finished and formed up at the far end of the drill hall, all three guards compared their counts. If they disagreed, they were marched though again. I then entered the figure on my clip-board. The total of POWs varied slightly from time to time, but during my tour of duty it was 956. That number is burned in my memory. God help us if we could only find 955! That total would never be paraded in the drill hall. Some would be on sick list, others at work in such places as the kitchen. Runners would make the rounds to include them in the total. During the count, Col. Hauk, the senior German officer responsible for discipline, and spokesman to the Canadian commandant, stood on the stage. The prisoners would not be dismissed until we were satisfied that all was in order. Any count disagreements or delays meant they had to stand there for long periods, and this of course irritated them. I was told that while the war was still on, some prisoners passing by the counters would quicken their pace and even start doubling up to confuse and harass their guards. But unless this was a ploy to cover and gain time for an escaper, it tended to raise the ire of their fellow prisoners, because they all had to stand there while the count was repeated. On one memorable occasion we were one short. We counted them all again, and scouts, including some POWs, were despatched on a search of the camp. As tension and the tempers of the standing POWs mounted, they glanced through their ranks speculating who was missing. A murmur rippled through to me…. “It’s the little engineer!” Then I remembered our most unusual prisoner - unusual because he was a civilian and no-one seemed to know why he was in this camp for German officers. The story was that he was the engineer on a train carrying German troops that got shot up by R.A.F. Typhoons and was then surrounded and captured by British troops. They did not know what to do with the civilian locomotive driver, so scooped him up with the military prisoners. He ended up in Wainwright. He was a very short stocky man, and naturally conspicuous among his uniformed fellow prisoners. As time dragged on and some of the prisoners sat on the floor, Col. Hauk paced the stage angrily, and asked to speak to me. He said that since we knew the identity of the missing man, there was no reason for not dismissing the parade. I refused. Standing Orders had to be followed. Finally, the large double doors of the drill hall opened, and we were treated to a most unusual sight. Silhouetted against the outside daylight, two large Germans marched in. Between them they carried the little engineer by the arms, his legs pedalling the air off the ground. The ranks of the POWs parted to let them pass, and they hurled epithets at the cause of their inconvenience. They marched right up to the stage and plunked the trembling man on the floor in front of Col. Hauk who glared down at him with legs apart and fists on his hips. It turned out that the searchers had found him sitting fast asleep on the toilet. I dismissed the parade, and as they filed out I walked over to the stage and stood behind the cringing engineer. The colonel looked at me and said crisply, “I shall take care of the matter, Lieutenant.” That was my cue to depart with my clip-board and my assistants, and as I went out the door I glanced back and saw the colonel still glaring down at the wretched engineer, and I wondered what punishment would be meted out. I hoped Col. Hauk had a sense of humour. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission Bald befanden wir uns wieder auf der Landstraße und marschierten rüstig gen Norden. Noch einmal wurden wir ein Stück Wegs mitgenommen. Schnell wurde es Nacht. Ein Strohschober diente als Lager. Wir waren bald eingeschlafen. Plötzlich fuhren wir hoch. Ein langgezogenes Heulen hatte uns geweckt. Jetzt vernahmen wir es wieder - ganz nahe - und dazwischen ein merkwürdiges Kläffen. Präriehunde, eine Schakalart, mußten es sein. "Stehen wir auf", meinte Heinz, "zum Schlafen kommen wir doch nicht mehr bei der Kälte." Wir fröstelten und rieben die klammen Hände. "Zu dumm, daß wir wegen der enggespannten Drähte nicht mehr anziehen konnten", bemerkte ich "aber das Durchschlüpfen durch den Zaun war schon so schwierig genug gewesen." Im Dunkeln trotteten wir auf der Landstraße weiter, die wie ausgestorben schien. Soon we found ourselves back on the country road and marching vigorously northward. Once again we found a ride for part of the way. Quickly it became night. A haystack served as camp. We had soon fallen asleep. Suddenly, we shot up. A long drawn out howl had awakened us. We heard it again - very close - and a strange yapping in between. It must be wild dogs, some type of jackal. "Let's get up," suggested Heinz, "we won't be getting back to sleep in this cold." We were freezing and rubbed our damp hands. "Too bad that because of the narrowly spanned wires we couldn't put on more clothes," I remarked "but slipping through the fence was already hard enough." In the dark, we jogged farther along the country road, which seemed deserted.

"The worst part was the thirst... Outside lay snow, only a few meters away and yet unreachable for us." (page 84) Image adapted from one that was available on Flickr as CC-BY (attribution license) but is now private. Music from Beethoven's Violin Concerto in D, Opus 61, first movement: http://www.musopen.com/music.php?type=piece&id=454

Here's an interesting bit of history that shows how cultural differences can affect how a good deed is perceived:

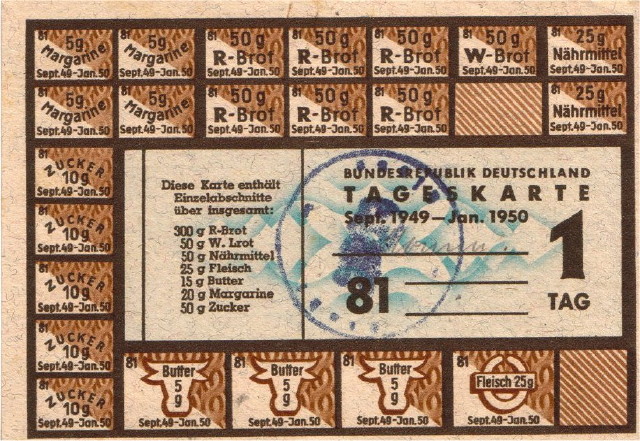

(I heard this story in the past, perhaps from my Uncle.) As noted yesterday, there were severe food shortages in Germany after the war. Those continued for several years. Here are some details from "The U.S. Army in the Occupation of Germany, 1944-1946" by Earl F. Ziemke.

The ration in the U.S. zone was 1,550 calories per day, but reduced grain imports would no longer support that.

("Clay" is General Lucius D. Clay, who went on to play a key role in the Berlin Airlift.) Here's a separate account (in German) about rations in Vienna, Austria in 1945:

In November 1947, the ordinary ration was up to 1,700 calories. Most restrictions were removed in 1950. Here is part 4 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (minor typos corrected) (Update: The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.) Dreary Prospects For a POWHowever, any harsh conditions and rigid regulations had softened greatly by the time I arrived at Wainwright. The war had ended several months before, and attitudes had changed considerably. Germany had lost the long and bloody war, and our unwilling guests were no longer considered a dangerous threat to our security. At that point in time, the only possible motive for escape was to become illegal immigrants to Canada, with the hope of melting undetected into our population. All thoughts, for captives and captors alike, were on salvaging all they could from ruined lives. For us, the victors, there were bright hopes in a country that despite the great cost of our victory, was spared the physical blight of war. For the vanquished, there was despair and uncertainty, knowing that their homeland was now largely in smoking ruins. It must have been a terrible thing to have suffered so much on far-flung battlefields and to know that it was all for nothing. They too were victims of the greatest episode of mass insanity in human history. It was not generally realized that officially these men were prisoners of the British, and they were being incarcerated in Canada at the request of the British Government for obvious reasons. In Britain they were short of food and space, and any escapers posed more of a threat to security in what was literally a war zone. Britain retained control, and their wishes had to be complied with. I was not aware at the time of an extraordinarily harsh and pointless order concerning the treatment of POWs that came from Britain after the war ended. I learned of this only recently from the reminiscences of former Wainwright POW Siegfried Osterwoldt. Rations were reduced to 900 calories per day, barely above subsistence level. The reasoning behind this is obscure. Was it to punish the Germans for the starvation and deprivation among war victims across Europe? To let them know what real hunger felt like after living so well on Canadian rations that they had difficulty buttoning their uniforms? I have no idea of what the Canadian authorities thought of this order from the British Government, but under the bilateral agreement the Canadians had no option but to comply. I learned recently that the American government at the same time imposed the same ration restrictions on the thousands of POWs they held in the U.S.A. One thing was certain - with the defeat of Germany and the liberation of our men from their POW camps, there was no danger of retaliation. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission The rations were apparently reduced to the level that prevailed in Germany at the time (due to the extreme food shortages after the war). That was also about what Allied POWs were receiving in German camps towards the end of the war. From his personal contacts with former German POWs (who were generally quite appreciative of their good treatment in Canada), David J. Carter adds:

|