|

|

July 2010 Archive

kunstvolle Falltüren waren in die Fußböden geschnitten worden, um bei Zählungen im Haus unbemerkt von einem Stockwerk ins andere zu gelangen - um sich dort anstelle des fehlenden Kameraden zum zweiten Male zählen zu lassen. Plötzlich wurden wir in unseren Gedanken unterbrochen; das Radioprogramm, das geräuschvoll aus dem Lautsprecher tönte - brach ab. Würden wir jetzt unseren Steckbrief hören? Die Eier schmeckten uns auf einmal nicht mehr. Auch nicht der Whisky, den unser Freund uns noch hinterher spendierte. Augenzwinkernd gestand er uns, er sei ein Deserteur. Aber als wir ihm nicht die Bruderhand reichten, die er wohl erwartet hatte, da wurde ihm, dem legalen Kanadier, anscheinend bange vor seiner Redseligkeit - und er verabschiedete sich rasch. Daß er auch uns für Deserteure gehalten hatte, war gar nicht so verwunderlich, denn zu jener Zeit hielten sich in den Wäldern Nordkanadas viele Deserteure auf, vornehmlich Franco-Kanadier aus den französischen Provinzen Kanadas, die sich geweigert hatten, nach Übersee zu gehen. artful trap doors cut into the floors to be able to move unnoticed from one floor to another while a count was going on in the house - to be counted there a second time in place of the missing comrade. Suddenly our thoughts were interrupted; the radio program that boomed noisily from the speakers - broke off. Would we now hear our escape announced? All of a sudden the eggs no longer tasted good. Nor did the whiskey that our friend had sprung for afterward. Winking, he confessed to us: he was a deserter. But when we didn't accept his brotherly handshake, which he had indeed expected, then he, the legal Canadian, seemed to regret that he was so talkative - and he made a quick farewell. That he took us for fellow deserters wasn't surprising, because at that time, many deserters were staying in the woods of Northern Canada, mainly Franco-Canadians from the French provinces of Canada, who had refused to go overseas.

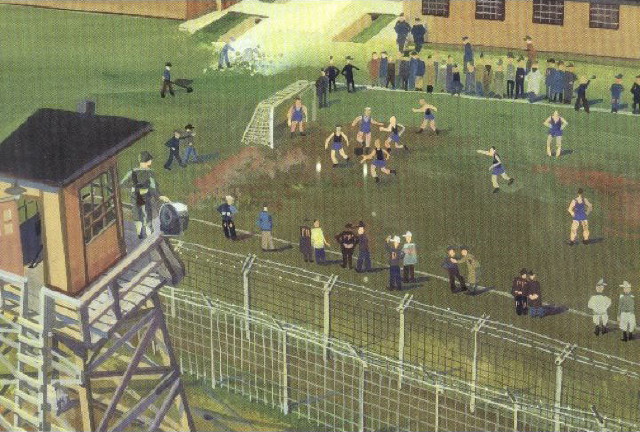

"'OK, into our hideout' ... the floorboards were put back into place above us, a crossbar was secured from below to make it impossible to lift our covering" (page 74) Images adapted from Mr. Thinktank and MNgilen at Flickr. Music from Beethoven's Violin Concerto in D, Opus 61, first movement: http://www.musopen.com/music.php?type=piece&id=454 Page 12 (posted last week) noted that Klaus Conrad and Heinz Meuche left behind two dummies as "stand ins" for the evening count. David J. Carter posted a great picture from a different camp:

Here's a worthwhile excerpt from an article that I've covered before:

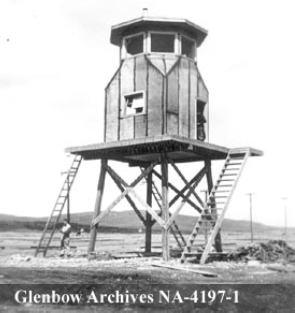

(The image is not from the article but I think it's a good match.) Here is part 3 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (Update: The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.) A Prisoner’s Paradise?The next morning was my first day on the job, and I was told to check all the sentries at the gates and in the guard towers. The towers were quite a climb. I was astounded to see scores of POWs streaming out the open gate of the POW compound carrying skis over their shoulders. NOW what was going on? The tower guard on duty was observing this calmly without a word. I scrambled down from the tower and hurried to the gate and the small building beside it through which the ski-laden POWs were trooping. I saw that each one was signing a form as he passed through. I picked one up and read it. It was printed in both English and German. I wish now that I had kept one. To the best of my recollection it said something to the effect… “I declare on my honour as a German Officer that I will not attempt to escape while outside the POW compound on this parole, that I will stay within the prescribed area, that I will not approach any civilians, that I will not go near the railroad tracks, and that I will return and report in to the gate not later than 4.00 o’clock. I acknowledge that any violation of this parole may result not only in the prescribed punishment for me but cancellation of this privilege for all German officers in this camp indefinitely.” Thereafter I became accustomed to watching them with my binoculars from the towers as they enjoyed themselves on the gentle slopes with skis supplied by, I believe, the Y.M.C.A., Red Cross, and other charitable organizations. Was this a prison camp or a resort? I often observed them stopping to look at their watches, wondering if they had time for one more slide down the slope before time was up. We had warned them that the gate would be closed at the appointed time, and anyone locked out would be declared an escapee in very serious trouble and in danger of being shot. The siren would then sound to alert the whole camp and army base. For those not involved in skiing, there were escorted exercise walks in large groups outside the wire. Not once was this parole ever violated deliberately. In the curious irony governing prisoner-of-war camps and the Geneva Convention, the parole ended as soon as they were back inside the stockade. Then they were legally and honourably entitled to use all their wits, guile, and resources to attempt escape, and in every way give their captors as much trouble as possible. Some considered it their duty, as they were still soldiers at war with their enemies. They could be shot while fleeing, but not after they had surrendered. Thirty days solitary confinement was the usual punishment for escape attempts. These were the rules of the game for both sides in World War II for signatories to the Geneva Convention. Compliance was monitored by a neutral “Protecting Power”, usually Switzerland, and reports were made to the respective governments of the belligerents. Generally, the rules were adhered to with correctness by both sides, but there were a number of tragic and brutal lapses involving mass murder of helpless Allied prisoners, including Canadians in Normandy, by the Nazi S.S. and the Gestapo. As is usual with crimes of the winning side, much less is known of the hundreds of thousands[1] of German prisoners left to perish in an open field surrounded by barbed wire without shelter, food, or water after the final German surrender on May 8, 1945. It is alleged that this apparent war crime was carried out on the orders of the Allied Commander-in-Chief, American General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission [1] This allegation was made prominent in a book published in 1989, and refuted by a panel of historians in 1990 (published as a book in 1992). From a subsequent article: "There was never any serious disagreement that the German POWs were treated badly by the U.S. Army and suffered egregiously in these camps in the first weeks after the end of the war. ... But there was NO AMERICAN POLICY to starve them to death as Bacque asserts and NO COVER UP either after the war." und wenn es mit den beiden Strohpuppen und ihren aufgesetzten Gipsköpfen, die bei der Zählung im dritten Glied mitgeführt wurden, nicht geklappt hatte, dann mußte uns die Polizei schon auf den Fersen sein. Anfang des Krieges, da hatten wir einmal mit einer solchen Puppe den Ausbruch eines Kameraden fünf Tage lang tarnen können - aber seither hatten auch unsere Bewachungsmannschaften allerlei dazu gelernt. Während der Zählung mußte jede Kolonne nach dem Abschreiten der Front durch den zählenden Sergeanten mehrere Schritte vorrücken - und ob die beiden mitgeführten Puppen mit ihren künstlichen Gelenken das mitmachen würden, ohne aufzufallen, war die Frage. Auf welche Ideen waren wir nicht schon gekommen, um die Kanadier bei den Zählungen zu täuschen; Köpfe aus Gips, aus Holz und aus Pappmachee waren modelliert worden, im Krankenrevier lagen lebensgroße Puppen, deren Brust sich in regelmäßigen Abständen hob und senkte, betätigt durch eine feine Schnur, die zum Nachbarbett führte, and if the two hay dolls with their gypsum heads that replaced us in the third column hadn't done the job, the police must already be on our heels. At the beginning of the war we were able to cover a comrade's escape with such a dummy for five days - but the guard teams had learned a lot since then. During the count, every column had to move a few steps forward after the inspection of the front by the counting sergeant - and whether the two carried dolls with their artificial joints would take part without being noticed - that was the question. Such ideas had we not already thought up to deceive the Canadians at roll call; gypsum heads on dummies modeled out of wood and paper mache, in the sick bay lay life-sized dolls, whose chests moved up and down at regular intervals, operated by a thin cord leading to the neighboring bed,

"But we were met with a new mishap; I twisted my knee. ... 30 miles still lay ahead of us; 30 miles of icy road between impenetrable forests, 30 miles of path through the wilderness without any human settlement, without any possibility of help if we couldn't go any farther, 30 miles of nothing but woods, snow and ice." (pages 60-61) Images adapted from --mike-- and pinkmoose at Flickr. (The second image is of the North Saskatchewan River at Edmonton.) Music from Beethoven's Violin Concerto in D, Opus 61, first movement: http://www.musopen.com/music.php?type=piece&id=454 Although German POWs often wore their military uniforms, it was important to have distinctive work clothing to make it harder to blend into the population if they escaped. From David J. Carter:

Jill Browne (and Robert Henderson in the comments) offer some additional details (and a fun cartoon) on The Uniform of the German POWs in Canada:

In 2009, The Military Museums in Calgary, Alberta featured an exhibit called "For You, the War is Over." In 2008 it was displayed at the Galt Museum and Archives in Lethbridge, Alberta.

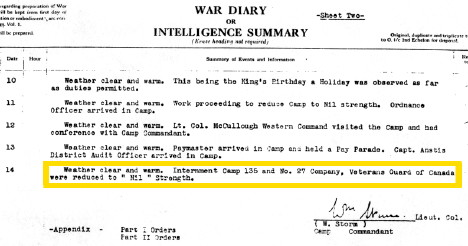

A few highlights are covered in the media kit. (pdf) For additional details, see the very interesting blog created by Jill Browne. Here is part 2 in our series of recollections by Canadian Lt. Leo L. Hamson, regarding his time as a guard at the Wainwright POW camp. (Update: The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.) I opened the series last week with his story of Klaus Conrad's escape, though this entry actually comes first. I think it must have taken place in the Winter of 1945-1946, i.e. after the war was over but before POWs were sent back to Germany. My Introduction to a World Behind Barbed WireI cannot now remember the date that I was posted to the Wainwright POW camp in Northern Alberta other than it was in the depth of winter. And I am not certain to this day that it was because they actually needed me, or because they did not know what else to do with a surplus 25-year-old artillery lieutenant recently returned from overseas who was declining to take his discharge but still had to earn his keep. On arrival at the railroad station, I was met by a private of the Veterans’ Guard Of Canada driving an open jeep and my trunk was slung in the back. As we entered the precincts of the camp in brilliant winter sunshine, I saw for the first time the great prisoner-of-war stockade consisting of two high fences about twelve feet apart. The massive posts and criss-crossed barbed wire enclosed several acres, with neat rows of barracks of the style that was standard for the Canadian Army, an equivalency for the POWs as prescribed by the Geneva Convention. At intervals along the fence were the formidable guard towers, large structures with several flights of wooden stairs to reach the top-most glassed-in deck from which the armed guards kept watch. It was a chilling sight. We passed a hockey rink set up outside the barbed wire stockade. A vigorous game was in progress. I commented to my driver, “Oh! I see you play hockey here.” “Yes sir!” he responded cheerily, “Today the guards are playing the POWs” I was too shocked to make any reply. Evidently fraternization with the enemy was alive and well in Wainwright Prisoner-of-War Camp 135. After getting installed in my room in the Officers’ Quarters, I went to the H.Q. building and reported to Major Shanks, the commandant of Veterans’ Guard of Canada No. 27 Company. While eyeing me up and down, he noted the empty holster on my belt and asked me where my revolver was. I said that after returning from overseas I saw no further need for lugging the heavy thing around and turned it in to the quartermaster in Calgary. He said, “Well, you will need one here. Go to the Q.M. Stores and draw one!” He indicated a building in the distance on a slight rise. On the road to the building, I saw three figures approaching, marching briskly. As they passed me, they saluted me smartly. I was stunned to realize they were German officers, and we were outside the stockade! I had automatically returned their salute, and then remembered the order of the vengeful General Eisenhower overseas that we were not to return the salutes of German prisoners. I had felt uncomfortable and embarrassed by this ban on what had always been considered an honourable military courtesy, even for a defeated enemy. When I entered the building, I found the usual quartermaster stores with shelves loaded with clothing, boots, equipment, tools, and weapons, all behind a long counter. At first there appeared to be no-one there, but suddenly a man at a desk behind the counter leaped to his feet and saluted me. I could hardly believe my eyes. He was dressed impeccably in the uniform of a German captain. Something was terribly wrong here. Mindful of what I had come for, I stammered, “There must be some mistake.” and turned to leave. Before I could reach the door, he called out in excellent English “You must be Lieutenant Hamson. I had a phone call from the Orderly Room about you. You have come for this.” He then reached under the counter and placed a regulation Smith and Wesson .38 caliber revolver on the counter. From a drawer he withdrew a box of cartridges, opened it to ensure that it was full and correct, and pushed the two items toward me. Then, as I stood there speechless, he pushed a book toward me. “Please sign here.” In a state of shock, I fumbled as I stowed the revolver in my holster, put the cartridges in my belt pouch, and walked unsteadily out the door. What kind of a place was this? Alice in Wonderland? A prisoner issuing me a GUN? When I went into the Orderly Room, I was in for a further shock. The people working busily at filing cabinets, typewriters and the switchboard were German officers. A Veteran’s guard lounged in a corner, smoking a pipe and reading a newspaper. When I encountered the commandant later, I let him know of my total astonishment to find the place apparently being run by the prisoners. “Of course!” he said, “The ones you see outside the stockade have signed a parole and they love having something useful to do. They are very good at it too…Teutonic efficiency and all that sort of thing, you know. And that gives us more time to spend in the mess drinking beer!” He then glanced at his watch. “My goodness! Time for four o’clock tea! Come along!” Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission Die gleiche Frage mochte er sich in Bezug auf uns beide vorlegen, denn bald begann er eine Unterhaltung und fragte so viel, daß wir achtgeben mußten, uns nicht in Widersprüche zu verwickeln. Es war am späten Nachmittag, als wir in Edmonton, der Hauptstadt Albertas und Metropole Nord-West-Kanadas eintrafen. Teils unserem eigenen Hunger, teils der freundlichen Aufforderung unseres Fahrers folgend, suchten wir eine kleine Speisebar auf. Beklommenen Herzens traten wir ein, denn wir hatten ja so gut wie kein Geld außer den paar Silbermünzen, die von illegalen Tauschgeschäften mit kanadischen Posten im Lager stammten. An der Theke bekamen wir Kaffee, Sandwiches und ein paar Eier, und als wir verlegen mit unseren wenigen Münzen klimperten, da bezahlte der junge Mann die Rechnung für uns mit. Es schlug sechs. In jähem Schrecken sahen wir uns an. Vor einer Stunde war Zählung gewesen im Kriegsgefangenenlager Wainwright ... He might have been asking himself the same question about us, because soon he started a conversation and asked so much that we must be careful not to get entangled in contradictions. It was late afternoon when we reached Edmonton, the capital of Alberta and metropolis of Northwestern Canada. Partly because of our own hunger, partly because of the driver's friendly invitation, we found a little diner. We entered with anxious hearts, since we had as good as no money except the few silver coins from our illegal trading activities with the Canadian guards inside the camp. At the counter we were served coffee, sandwiches and some eggs, and when we sheepishly jingled our few coins the young man paid the bill for us. The clock struck six. In sudden fear, we looked at each other. An hour ago the count had taken place in the Wainwright POW camp ...

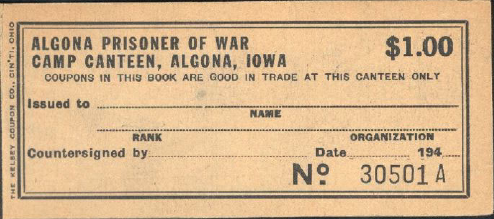

"An attempt to get to the open waters through the broad belt of reeds (in order to swim across the river) failed. I sunk ever deeper into the marsh and was nearly pulled under there. The black brew reached up to my chest, stinking bubbles rising up (and) by gathering all my strength I pulled myself back to the shore again using the reeds." (page 49) Images adapted from randwill, Gilder, clairity, avramishin at Flickr. (The middle 2 were composited: black brew in the front, shoreline in the back.) This music is from a different composer than previous videos: Beethoven's Violin Concerto in D, Opus 61, first movement: http://www.musopen.com/music.php?type=piece&id=454 Traces assembled some interesting facts on money at Camp Algona. From Lt. Col. Arthur T. Lobdell, Commandant:

Some details:

There's lots more in the slide show by Steve Feller: Scrip of the PW Camp at Algona, IA. (Flash required) Here's another part of camp life covered by the Geneva Convention. (emphasis added)

Lieutenant Leo Hamson returned to Canada after fighting in Europe, and was sent to Camp Wainwright as a guard. This entry is the first in a series, reprinted with permission. (emphasis added; 1 paragraph break added; 1 typo corrected) (Update: The full set of Recollections is back online, with photos.) A Brilliant EscapeAt dinner one night in the Officers’ Mess, I was regaled with the story of a successful escape by two POW officers that occurred when Wainwright first opened for business. The tale was told by the Veterans’ Guard officers with great relish and obvious admiration. It seems that a trainload of POWs arrived before the camp construction was quite finished, much to the consternation of the senior Canadian officer. The buildings were complete, but the stockade fences were not. The barbed wire was still being strung by the army engineers. The exasperated Canadian colonel ordered the POWs herded into their barracks with armed guards at the doors until the wiring was finished. The POWs watched the work from the windows. They noted that the khaki denim material of the work coveralls worn by the Canadians was of the same material covering the mattresses on their double-decker army beds. The senior German officer put out a call for anyone with tailoring experience. Hans Pfeffel stepped forward, and very soon had fashioned passable replicas of the coveralls. These were donned by Lt. E. Meuche and Lt. Klaus Conrad. While the others feigned a scuffle among themselves to distract the guards, these two slipped out and joined the fencing crew, giving a friendly wave to the tower guards as they passed under them. The guards cheefully returned the gesture. They unrolled a large spool of barbed wire along the line of posts, but veered from the line towards a copse of trees, then bolted unnoticed. They reached the railroad tracks and leaped aboard a passing freight train. Knowing nothing of Alberta geography[*], the next train they boarded was heading north to Lesser Slave Lake before they realized they would never reach the Fatherland that way. They caught a south-bound train, and were not apprehended until a month later in Gary Indiana. They were not returned to Wainwrght, but to the camp at Gravenhurst. There was a strange post-script to this story. Hans Pfeffel returned to Canada, settled in Coaldale, in Southern Alberta, opened a clothing store, and raised a family. He had a major part in the National Film Board documentary “The Enemy Within,” which I shall refer to later, and also provided some harmonica background music for the film. As my son-in-law now residing in England was born and raised in the small town of Coaldale, I was amazed when my inquiries revealed that the two families had been friends for years. Last year, although battling terminal cancer, Hans was determined to meet us, and made the very long journey to Edmonton with his wife, daughter, and son-in-law. We were joined at a luncheon in our garden by another former Wainwright POW, Siegfried Osterwoldt and his wife, and by Eva Colmers, who made and directed the film. A few weeks later, Hans passed away. We shall be forever grateful for his valiant effort in making the arduous journey that made possible an unforgettable reunion after nearly six decades. Copyright 2004 by Leo Hamson; used with permission * I think that heading north was planned, but in any case it's great to have an account direct from the Canadian side. "Den Sergeanten möchte ich sehen, wenn er feststellt, daß ich ihm schon wieder durchgegangen bin", entgegnete ich "aber ein verdammtes Gefühl in der Kehle war das, als er vorhin auf uns zukam. Und noch sind wir in bedrohlicher Nähe des Lagers, hoffentlich kommt bald ein Auto und nimmt uns mit." "Per Anhalter fahren" ist ein etwas umständlicher deutscher Ausdruck. Er ist sicherlich noch nicht alt. Die Amerikaner haben ein Verbum dafür: "to hitchhike", und das zeigt, wie gang und gäbe bei ihnen diese Reisemethode ist. Wir gingen also die Straße entlang und bald kam auch ein etwas klappriger Wagen, der sofort bereitwillig anhielt. "Going to Edmonton?" - "Fahren Sie nach Edmonton?" "That's right", sagte der einzige Insasse und nahm uns mit. Er war ein junger Mann, kaum älter als wir selber, und übrigens voll strotzender Gesundheit. Wieso war er nicht Soldat? "I want to see the sergeant when he finds out that I've slipped through his fingers again," I replied "but I had such a damned feeling in my throat when he was approaching us earlier. We're still dangerously close to the camp, hopefully a car comes soon and takes us along." "Per Anhalter fahren" is a somewhat circuitous German expression. It certainly can't be very old yet. The Americans have a verb for it: "to hitchhike," and that shows how commonplace this method of travel is with them. So we went alongside the road and soon a somewhat rickety car came along, that immediately stopped, unhesitant. "Going to Edmonton?" "That's right," said the sole occupant and took us with him. He was a young man, barely older than us and, incidentally, brimming with health. How was he not a soldier?

"The guards turned around again, coming back step by step. Ever closer they moved. A few steps away from me they stopped. My heart pounded in my throat; I hardly dared to breathe." (page 42) Images (loosely!) adapted from isafmedia, soldiersmediacenter, soldiersmediacenter, and thejointstaff at Flickr Music from Bach's Toccata Adagio Fugue: http://www.musopen.com/music.php?type=piece&id=468 According to the 1929 Geneva Convention, captured troops were to receive the same housing and food as the country's own troops. Here are some excerpts from SECTION II - PRISONERS OF WAR CAMPS. (emphasis added) Art. 10. Prisoners of war shall be lodged in buildings or huts which afford all possible safeguards as regards hygiene and salubrity. The premises must be entirely free from damp, and adequately heated and lighted. All precautions shall be taken against the danger of fire. As regards dormitories, their total area, minimum cubic air space, fittings and bedding material, the conditions shall be the same as for the depot troops of the detaining Power. Life was not easy after returning to Germany. Here are two letters from former POWs at Camp Aliceville in Alabama. June 8, 1947 September 15, 1947 A full year after "Victory in Europe" day... Excerpts from May 1946: (emphasis added; skipped days are not marked; all typos in original)

June

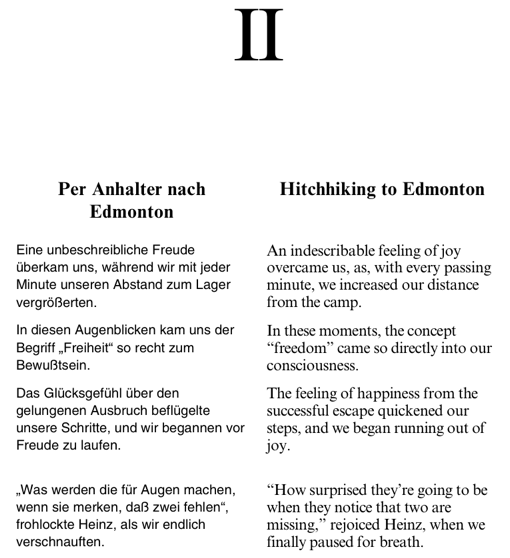

(Page 8 is blank so that this chapter starts on the right-side page.) Chapter II Per Anhalter nach Edmonton Eine unbeschreibliche Freude überkam uns, während wir mit jeder Minute unseren Abstand zum Lager vergrößerten. In diesen Augenblicken kam uns der Begriff "Freiheit" so recht zum Bewußtsein. Das Glücksgefühl über den gelungenen Ausbruch beflügelte unsere Schritte, und wir begannen vor Freude zu laufen. "Was werden die für Augen machen, wenn sie merken, daß zwei fehlen", frohlockte Heinz, als wir endlich verschnauften. Hitchhiking to Edmonton An indescribable feeling of joy overcame us, as, with every passing minute, we increased our distance from the camp. In these moments, the concept "freedom" came so directly into our consciousness. The feeling of happiness from the successful escape quickened our steps, and we began running out of joy. "How surprised they're going to be when they notice that two are missing," rejoiced Heinz, when we finally paused for breath.

"Those nights when the Northern Lights interrupted the darkness for minutes at a time will remain especially unforgettable; a fairy tale-esque gleam and twinkle ran across the sky and we were witness to this phenomenon only visible in the Arctic regions." (page 33) Images adapted from Jökull Másson, nick_russill and Image Editor at Flickr Music from Bach's Toccata Adagio Fugue: http://www.musopen.com/music.php?type=piece&id=468 |